We use cookies to make your experience better. To comply with the new e-Privacy directive, we need to ask for your consent to set the cookies.

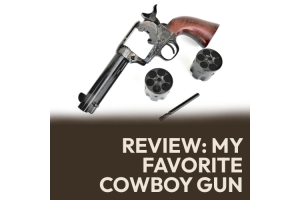

Taylor's 1873 Cattleman .44-40 Review

A Faithful Reproduction of Early Peacemakers

Written By Jeremy Clough

Sometimes, going back to the beginning helps flesh out where you are. This is as true of defensive pistolcraft as anything else, which is still a relatively recent discipline. For example, the point-shooting/combative/threat-focused guys look backward to Col. Rex Applegate. He, in turn, studied Wild Bill Hickok while developing the OSS shooting curriculum. Thus, in my own quest to go back to first things, I found myself in Arizona shooting a 5×5 drill at Gunsite with a single-action .44-40 under the watchful eye of Rangemaster and End of Trail champion Lew Gosnell. Oh, and it was snowing.

I’ve been spoiled by really good single actions, as have all of us who arrived after the transfer bar safety. I’ve never had to deal with “load-one-skip-one” sixguns that are really five shooters because they’re unsafe to have a cartridge beneath the hammer. My Rugers are plenty strong, and have smooth actions and good sights (usually by Hamilton Bowen) that make them as easy to shoot well as any big bore sixgun is. What they are not is an accurate picture of what the earliest fighting revolvers were like.

The 1st Gunfighter’s Gun

Technically, the cap’n’ball 1851 Navy is the first gunfighter’s gun, but the Peacemaker is really where the West came of age. Since original Colts cost more than my car and, being iron, aren’t the safest to shoot, I turned to Taylor’s Firearms to get as close as reasonable to an early Peacemaker. But first, a bit about the Colt it’s based on. The 1873, aka Single Action Army, or better yet, “Peacemaker,” is a gun that has long needed no introduction, but after long enough, perhaps it does again.

Colt lagged behind S&W in the revolver game because they let former employee Rollin White escape, with his patent for a bored-through cylinder sidelining them for years from making a cartridge gun. In the meantime, gunsmiths (including the stray Colt engineer or two) created various cartridge conversions to update the massive flood of nearly a half-million or so black powder Colts washing around after the Civil War. Once White’s patent expired, they basically applied the same principles to create the 1872, a transitional gun that looks a lot like an open-topped Peacemaker. It was chambered in the .44 Rimfire used in Henry rifles because there was also quite a bit of that in the post-war detritus and because it made sense to have both guns chambered in the same caliber. This theme reappeared with the 1873 Winchester and the Peacemaker that appeared in the same year, though it took about four years before it was offered in the same .44-40 caliber as the popular Winchester levergun.

The Peacemaker debuted in .45 Colt, with the solid top strap and screwed-in barrel of the Remington 1858 in place of the arbor-and-key arrangement of the earlier Colts. Instead of taking the barrel off to remove the cylinder, the base pin around it revolved and could be pulled forward, allowing the cylinder to roll out to the side. Later Colts (and virtually all subsequent single actions) use a spring-loaded plunger to hold the base pin in, but the earliest Colts, called “black powder” guns because the cartridges they fired were not yet loaded with smokeless powder, use a simple set screw.

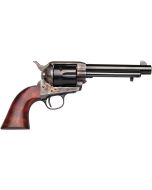

Cattleman Old Model

As does the Taylor’s Cattleman Old Model, which is also equipped with the early, round “bullseye” ejector rod. A favorite of the late Mike Venturino, the bullseye design is much easier on the fingers than the later tab and teardrop styles. Made to Taylor’s specifications by Uberti, the Old Model also has a tapered front sight and the original-style lockwork. As referenced earlier in this article, early Colts allowed the firing pin to rest on the primer of the cartridge beneath the hammer, which is extremely dangerous. A half-cock notch was intended to keep the hammer safely back but is fragile enough to break if the gun is dropped. Hence the practice of loading one cartridge, skipping one, then loading four and cocking the hammer to lower it safely on an empty chamber. Ruger’s transfer bar safety eliminated this issue on modern sixguns, but on an early gun, it’s the only safe way — and that includes the Cattleman Old Model. The grips are wood and one-piece style, the action makes an appropriate number of clicks, and while the trigger had some roughness in it at first, with use, it smoothed out to a very pleasant 2 lbs., 9.9 oz. as measured by my Lyman scale.

Leather

For leather, I went to Frontier Gunleather. John Bianchi was a long-time aficionado of the West whose personal collection formed a major part of the Gene Autry Museum of Western Heritage. After retiring from the modern holster company that bears his name, he founded Frontier to make handcrafted Western-style leather gear, later turning it over to master craftsman Matt Whitaker, who’s been with the company since 2000.

I ordered the Bill Tilghman rig, named after the famed lawman whose career began in Dodge City in the 1870s and continued in Oklahoma, where he became known as one of the “Three Guardsmen,” who tirelessly pursued the Daltons, Doolins and other famed badmen of the era until they were captured or killed. Tilghman served until 1924 when he was killed in the line of duty at 70 years old. By a dirty cop, no less.

This was my first real exposure to Whitaker’s work, and now I want an excuse to buy more. It isn’t one of his more exotic carved rigs, but the design and craftsmanship are simply superb, from the careful chamfering to the way the stitching blends seamlessly into the border grooves on the chape. It’s solidly built enough to support the weight of the gun and loaded cartridge loops without being unnecessarily heavy and carried comfortably all day long.

Range Trials

Part of the reason I ordered a .44-40 instead of .45 is that I was scheduled to attend a meeting of the Gunsite Irregulars, a shooting event for which I needed a revolver and lever gun in the same caliber, and I already had a .44 caliber Winchester. I had some Black Hills 200-grain cowboy ammo on hand, as well as components provided by Starline Brass and Hunters Supply, who had sent cast lead bullets in 160, 200- and 240-grain weights. While modern .44-40s are made from the same barrel stock as the larger .44 Special and Magnums, traditionally, the .44-40 is loaded with a smaller bullet such as the 0.427″ slugs from Hunters Supply.

The standard load fires a 200-grain around 1,000 fps from a handgun, but I went with lighter loads using Titegroup, Unique and 231, and shot around 300 rounds total. The 160s were quite soft shooting out of the 2-lb., 5-oz. revolver, probably trundling out of the bore in the 800 fps range, but hit about 10″ low at 25 yards. My 200s went 8″ low and the 240s, 6″. And herein lies a lesson. The rudimentary sights on early sixguns seldom sent the bullet where indicated, and part of the sixgun craft is developing a specific load that will hit to point of aim with each individual gun. The late (and it hurts to have to type that) Mike Venturino has an excellent description of the process in his book on shooting Colt single actions, and I’ll be working on that with this gun, as I’d rather do that than file the front sight.

I struggled shooting 25-yard groups and couldn’t seem to do better than 4″ but did much better at 7, putting five rounds into about 0.57″ from standing. Do the math, and the gun shoots twice as well at 25 yards as I did that day.

I’d like to blame the snow, but that was a different day. And as much as I would like to have descended from the high desert with earth-shattering revelations learned, I haven’t yet distilled the experience into principles I haven’t written about before.

But I did learn this: I really like the challenge. And we’ve got it really good.

https://americanhandgunner.com/handguns/taylors-1873-cattleman-44-40-review/