We use cookies to make your experience better. To comply with the new e-Privacy directive, we need to ask for your consent to set the cookies.

Review: Taylors & Company "1858 The Ace"

ODE TO THE WILD WILD WEST? WRITTEN BY FRANK JARDIM

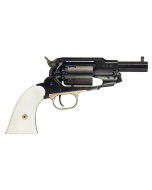

When I first saw the Taylor’s & Company’s snub-nosed, cap & ball 1858 Remington with a conversion cylinder to shoot .45 Colt, it instantly struck me as the kind of gun you would expect James West or Artemus Gordon to pull from nowhere in The Wild Wild West action/adventure TV series that ran in the late 1960s.

The show, conceived as “James Bond On Horseback,” was wildly fun fantasy blending Victorian sci-fi gadgetry with the Western genre. West and Gordon, played by Robert Conrad and Ross Martin respectively, were Secret Service agents with cutting edge technology and a propensity for aggressive solutions to their various law enforcement challenges. They had their own steam-locomotive-driven train to travel around the country in while foiling the plans of various villains. My brother and I, like most boys, were devoted fans. As an adult, I realized this unique show actually helped create the “Steampunk” genre we have today.

Back To The Future

Called “1858 The Ace” and sporting a 3″ barrel, Taylor’s pistol sports a slick finger-tip operated cylinder pin release installed where the loading lever originally went. With no loading lever, this pistol just demands a conversion cylinder to allow it to fire metallic cartridges.

Taylor’s offers these for all their cap & ball revolvers as well as the Ruger Old Army revolver. The bore of a replica .44 1858 Remington is actually 0.452″, which makes it ideal for .45 Colt or .45 Schofield whose bullet diameters typically fall in the 0.452″ to 0.455″ range. For accuracy, you want your cast bullets to match the groove diameter or be a few thousandths larger for a good gas seal and full engagement with the rifling.

Speaking of cast bullets, a word of warning is in order. Taylor’s states very clearly you should not use jacketed bullets or +P ammunition in this pistol because you might damage the gun. They specifically mention the possibility of cracking the forcing cone. The conversion cylinder is plenty strong, being made of 4150 arsenal-grade steel but the handgun itself is only proofed for black powder, lead bullet loads. It sounds like prudent guidance to me. This shouldn’t be your go-to gun for concealed carry anyway. With a 3″ barrel, this shootin’ iron is still 9″ long and weighs over 36 oz.!

Cartridge Power

The ease with which an 1858 Remington cylinder is removed, compared to a cap & ball Colt, makes them more practical to use with conversion cylinders. The conversion cylinder itself is a fine piece of precision machine work worthy of Artemus Gordon’s railcar laboratory. The body of the cylinder is notched out to expose the edge of each cartridge when assembled so the shooter can see which chambers are loaded.

Six individual firing pins are installed in the backplate, which indexes with the cylinder body at two points, a boss at the center and a pin on the perimeter. Though there’s a slight amount of side-to-side play between the cylinder body and backplate, I don’t see it causing any timing issues because the cylinder is held in alignment by the bolt, not the hand. The hand’s job is just to advance the cylinder when the hammer is cocked.

Unlike the cap & ball cylinder, the cartridge conversion cylinder has NO slots between the chambers to rest the hammer in so you can’t safely carry the conversion cylinder with all six rounds loaded. When the conversion cylinder is installed, unless at half-cock, the hammer is resting directly on the firing pin. Therefore, it’s safety-critical only five shots be loaded so the hammer can rest on an empty chamber, just like you would with any Old West metallic cartridge single-action revolver. The chamber next to the indexing pin is a good choice to leave empty because it’s the easiest to keep track of when the cylinder is assembled.

The cylinder is installed with the revolver at half-cock by inserting it from the right side of the frame and turning it clockwise so the backplate pushes the hand up and out of the way. This sounds trickier than it really is. Once the cylinder is past the hand and centered in the frame window, push the cylinder pin in until it latches. Then carefully ensure the empty chamber is actually under the hammer before letting it down with your thumb.

Had “1858 The Ace” been around when The Wild Wild West was still on the air, I could easily imagine former Union Army officer James West keeping it tucked under his coat, concealed for contingencies. The Remington-Elliot derringer in his boot heels notwithstanding, West was a belt holster kind of guy.

By contrast, I’d expect Gordon to have some kind of complex mechanical holster, more likely than not with an automatic presentation feature that includes a polished brass scissor arm extending from beneath his vest. As cool as that would be, I didn’t have the shop time to invent it; so, I took the cross draw holster to the range.

Shootin’

Starting with the butt of the pistol grip over my belt buckle, the #117 Keegan Crossdraw holster from Triple K allowed for a speedy presentation but the speed of my shooting wouldn’t have impressed anyone. The pistol comes with a heavy hammer spring that will surely beat the most resistant hard primer to ignition and as you would expect, takes a determined and muscled thumb to cock. An action job would speed it up considerably. In fast-as-I-could point shooting at seven yards, I was able to keep my shots on the silhouette target. The pistol’s real capabilities became clear when I got out the Caldwell Pistolero rest and did some 25 yard testing from the bench.

The trigger broke at just a little over 3 lbs., and despite some creep, I was able to make five shot groups between 3.9″ and 4.7″ measured center-to-center. Federal’s lead, hollow point, semi-wadcutters produced the tightest groups, the smallest being 3.2″, with four of those shots making a cloverleaf inside of an inch! Average velocity was a mild 775 feet-per-second. The classic .45 Colt load, Winchester’s Super-X with a 255-grain lead round-nose bullet averaged 4.7″ groups, clocking a little less velocity at 715 feet-per-second. The Ace’s 3″ barrel was costing me at least 100 feet-per-second of velocity. I bet the muzzle flash from it at night would be impressive.

The sights out of the box were well regulated. At seven yards, the pistol shot to point of aim. At 25 yards it was 5″ low. My test gun needed no windage adjustment but this pistol, made by Pietta, has the front sight dovetailed in allowing for some adjustment.

MSRP for the gun is $358 with the classy white PVC grips. It’s also available with smooth or checkered walnut stocks. The .45 Colt/.45 Schofield cartridge conversion cylinder has an MSRP of $240.